I bought myself a New Nintendo 3DS (not just a brand new one, but the device named "New Nintendo 3DS"). I had been for quite a long time pondering about buying a 3DS, and the new version of the console finally gave me the impetus of buying one.

One of the major new hardware features of the console is better 3D via eye-tracking. The original 3DS has a parallax barrier 3D screen (which in practice means that the 3D effect is achieved without the need of any kind of glasses). Its problem is that it requires a really precise horizontal viewing angle to work properly. Deviate from it even a slight bit, and the visuals will glitch. The New 3DS improves on this by using eyetracking, and adjusting the parallax barrier offset in real time depending on the position of the eyes. This way you can move the device or your head relatively freely, and the 3D effect is not broken. It works surprisingly well. Sometimes the device loses track of your eyes and the visuals will glitch, but they fix themselves when it gets the track again. (This happens mostly if you eg. look away and then back at the screen. It seldom happens while playing. It sometimes does, especially if the lighting conditions change, eg. if you are sitting in a car or bus and the position of the sun changes rapidly, but overall it happens rarely.)

There is, however, another limitation to the parallax barrier technology, which even eyetracking can't fix: The distance between your eyes and the screen has to be within a certain range. Any closer or farther, and the visuals will start glitching once again. There is quite some leeway in this case, ie. this range is relatively large, so it's not all that bad. And the range is at a relatively comfortable distance.

Curiously, the strength of the 3D effect can be adjusted with a slider.

Some people can't use the 3D screen because of physiological reasons. Headaches are the most common symptom. For me this is not a problem, and I really like to play with full depth.

There are a few situations, however, where it's nicer to just turn the 3D effect off. For instance if you would really like to look at the screen up close. Or quite far (like when sitting on a chair, with the console on your lap, quite far away from your eyes.) Or for whatever other reason.

The 3D effect can be turned completely off, which makes the screen completely 2D, with no 3D effect of any kind: Just slide the slider all the way down, and it turns the 3D effect completely off.

Except it didn't do that! Or so I thought for one and a half year.

You see, whenever the 3D effect is turned on, no matter how small the depth setting, the minimum/maximum eye distance problem would always be there. If you eg. look at the screen too closely, it would glitch, even if so slightly, and quite annoyingly. With a lower depth setting the glitching is significantly less, but it's still noticeable. Some uneven jittering and small blinking happens if you move the device or your head at all, when you are looking at the screen from too close (or too far).

Even though I put the 3D slider all the way down, the artifacts were still there. For the longest time I thought that this might be some kind of limitation of the technology: Even though it claimed that the 3D could be turned off, it wasn't really possible fully.

But the curious thing was that if I played any 2D game, with no 3D support, the screen would actually be pure 2D, without any of the 3D artifacts and glitching in any way, shape or form. It would look sharp and clean, with no jittering, subtle blinking, or anything. This was puzzling to say the least. Clearly the technology is capable of showing pure and clean 2D, with the 3D effect turned completely off. But for some reason in 3D games this couldn't be achieved with the 3D slider.

Or so I thought.

I recently happened to stumble across an online discussion about turning off the 3D effect in the 3DS, and one poster mentioned that in the 3DS XL there's a notch, or "bump", at the lower end of the slider, so that you have to press it a bit harder, and it will get locked into place.

This was something I didn't know previously, but somehow this still didn't light a bulb in my head. However, incidentally, when I was playing with the 3D slider, I happened to notice, when I looked at it from a better angle, that the slider wasn't actually going all the way down. There was a tiny space between the slider and the end of the slit where it slides, even though I thought I had put it all the way down.

Then it dawned on me, and I remembered that online discussion (which I had read just some minutes earlier): I pressed the slider a bit harder, and it clicked into its bottommost position. And the screen became visibly pure and clean 2D.

I couldn't help but laugh at myself. "OMFG, I have been using this damn thing for a year and a half, and this is the first time I notice this?" (Ok, I didn't think exactly that, but pretty much the sentiment was that.)

So yeah, the devil is in the details. And sometimes we easily miss those details.

I have to wonder how many other people don't notice nor realize this.

Saturday, July 16, 2016

Thursday, July 7, 2016

Which chess endgame is the hardest?

In chess, many endgame situations with only very few pieces left can be the bane of beginner players. And even sometimes very experienced players as well. But which endgame situation could be considered the hardest of all? This is a difficult (and in many ways ambiguous) question, but here are some ideas.

Perhaps we should start with one of the easiest endgames in chess. One of the traditional endgame situations that every beginner player is taught almost from the very start:

This is an almost trivial endgame which any player would be able to play in their dreams. However, let's make a small substitution:

Now it suddenly became significantly more difficult (and one of the typical banes of beginners). In fact, the status of this position depends on whose move it is. If it's white to move, white can win in 23 moves (with perfect play from both sides). However, if it's black to move, it's a draw, but it requires very precise moves from black. (In fact, there is only one move in this position for black to draw; every other move loses, if white plays perfectly.) These single-pawn endings can be quite tricky at times.

But this is by far not the hardest possible endgame. There are notoriously harder ones, such as the queen vs. rook endgame:

Here white can win in 28 moves (with perfect play from both sides), but it requires quite tricky maneuvering.

Another notoriously difficult endgame is king-bishop-knight vs. king:

Here white can also win in 28 moves (with perfect play), but it requires a very meticulous algorithm to do so.

But all these are child's play compared to the probably hardest possible endgame. To begin with, king-knight-knight vs. king is (excepting very few particular positions) a draw:

But add one single pawn, and it's victory for white. But not a white pawn. A black pawn! And it can be introduced in quite many places, and white will win. As incredible as that might sound:

Yes, adding a black pawn means that white can now win, as hard as that is to imagine.

(The reason for this is that the winning strategy requires white to maneuver the black king into a position where it has no legal moves, several times. Without the black pawn this would be stalemate. However, thanks to the black pawn, which black is then forced to move, the stalemate is avoided and white can proceed with the mating sequence.)

But this is a notoriously difficult endgame. So difficult, that even most chess grandmasters may have difficulty with it (and many might not even know how to do it). It is so difficult that it requires quite a staggering amount of moves: With perfect play from both sides, white can win in 93 moves.

Perhaps we should start with one of the easiest endgames in chess. One of the traditional endgame situations that every beginner player is taught almost from the very start:

This is an almost trivial endgame which any player would be able to play in their dreams. However, let's make a small substitution:

Now it suddenly became significantly more difficult (and one of the typical banes of beginners). In fact, the status of this position depends on whose move it is. If it's white to move, white can win in 23 moves (with perfect play from both sides). However, if it's black to move, it's a draw, but it requires very precise moves from black. (In fact, there is only one move in this position for black to draw; every other move loses, if white plays perfectly.) These single-pawn endings can be quite tricky at times.

But this is by far not the hardest possible endgame. There are notoriously harder ones, such as the queen vs. rook endgame:

Here white can win in 28 moves (with perfect play from both sides), but it requires quite tricky maneuvering.

Another notoriously difficult endgame is king-bishop-knight vs. king:

Here white can also win in 28 moves (with perfect play), but it requires a very meticulous algorithm to do so.

But all these are child's play compared to the probably hardest possible endgame. To begin with, king-knight-knight vs. king is (excepting very few particular positions) a draw:

But add one single pawn, and it's victory for white. But not a white pawn. A black pawn! And it can be introduced in quite many places, and white will win. As incredible as that might sound:

Yes, adding a black pawn means that white can now win, as hard as that is to imagine.

(The reason for this is that the winning strategy requires white to maneuver the black king into a position where it has no legal moves, several times. Without the black pawn this would be stalemate. However, thanks to the black pawn, which black is then forced to move, the stalemate is avoided and white can proceed with the mating sequence.)

But this is a notoriously difficult endgame. So difficult, that even most chess grandmasters may have difficulty with it (and many might not even know how to do it). It is so difficult that it requires quite a staggering amount of moves: With perfect play from both sides, white can win in 93 moves.

"Tank controls" in video games

3D games are actually surprisingly old. Technically speaking some games of the early 1970's were 3D, meaning they used perspective projection and had, at least technically speaking, three axes of movement. (Obviously back in those days they were nothing more than vector graphics drawn using lines and sprites, but technically speaking they were 3D, as contrasted to purely 2D games where everything happens on a plane.) I'm not talking here about racing games that give a semi-illusion of depth by having the picture of a road going to the horizon and sprites of different sizes, but actual 3D games using perspective projection of rotateable objects.

As technology advanced, so did the 3D games. The most popular 3D games of the 80's were mostly flight simulators and racing games (which used actual rotateable and perspective-projected 3D polygons), although there were obviously attempts at some other genres as well even back then. It's precisely these types of games, ie. flight simulators and anything that could be viewed as a derivative, that seemed most suitable for 3D gaming in the early days.

It is perhaps because of this that one aspect of 3D games was really pervasive for years and decades to come: The control system.

What is the most common control system for simple flight simulators and 3D racing games? The so-called "tank controls". This means that there's a "forward" button to go forward, a "back" button to go backwards, and "left" and "right" buttons to turn the vehicle (ie. in practice the "camera") left and right. This was the most logical control system for such games. After all, you can't have a plane or a car moving sideways, because they just don't move like that in real life either. Basically every single 3D game of the 80's and well into the 90's used this control scheme. It was the most "natural" and ubiquitous way of controlling a 3D game.

Probably because of this, and unfortunately, this control scheme was by large "inherited" into all kinds of 3D games, even when the technology was used in other types of games, such as platformers viewed from third-person perspective, and even first-person shooters.

Yes, Wolfenstein 3D, and even the "grandfather" of first-person shooters, Doom, used "tank controls". There was no mouse support by default (I'm not even sure there was support at all, in the first release versions), and the "left" and "right" keys would turn the camera left and right. There was support for strafing (ie. moving sideways while keeping the camera looking forward), but it was very awkward: Rather than having "strafe left" and "strafe right" buttons, Doom instead had a toggle button to make the left and right buttons strafe. (In other words, if you wanted to strafe, you had to press the "strafe" button and, while keeping it pressed, use the left and right buttons. Just like using the shift key to type uppercase letters.) Needless to say, this was so awkward and impractical that people seldom used it.

Of course all kinds of other 3D games used "tank controls" as well, including many of the first 3D platformers, making them really awkward to play.

For some reason it took the gaming industry a really long time to realize that strafing, moving sideways, was a much more natural and convenient way of moving than being restricted to only being able to move back and forward, and turning the camera. Today we take the "WASD" key mapping, with A and D being strafe buttons, for granted, but this is a relatively recent development. As late as early 2000's some games still hadn't transitioned to this more convenient form of controls.

The same goes to game consoles, by the way. "Tank controls" might even have been even more pervasive and widespread there (usually due to the lack of configurable controller button mapping). There, too, it took a relatively long time before strafing became the norm. The introduction of twin stick controllers made this transition much more feasible, but even then it took a relatively long time before it became the standard.

Take, for example, the game Resident Evil 4, released in 2005 for the PlayStation 2 and the GameCube, both of which had twin stick controllers. The game still used tank controls, and had no strafing support at all. This makes the game horribly awkward and frustrating to control; even infuriatingly so. And this even though modern twin-stick controls had already been the norm for years (for example, Halo: Combat Evolved was published in 2001.)

Nowadays "tank controls" are only limited to games and situations where they make sense. This usually means when driving a car or another similar vehicle, and a few other situations.

And not even always even then. Many tank games, perhaps ironically, do not use "tank controls". Instead, you can move the vehicle freely in the direction pressed with the WASD keys or the left controller stick, while keeping the camera fixated in its current direction, and which can be rotated with the mouse or the right controller stick (and which usually in such games makes the tank aim at that direction). In other words, direction of movement and direction of aiming are independent of each other (and usually the tank aims at the direction that the camera is looking). This makes the game a lot more fluent and practical to play.

As technology advanced, so did the 3D games. The most popular 3D games of the 80's were mostly flight simulators and racing games (which used actual rotateable and perspective-projected 3D polygons), although there were obviously attempts at some other genres as well even back then. It's precisely these types of games, ie. flight simulators and anything that could be viewed as a derivative, that seemed most suitable for 3D gaming in the early days.

It is perhaps because of this that one aspect of 3D games was really pervasive for years and decades to come: The control system.

What is the most common control system for simple flight simulators and 3D racing games? The so-called "tank controls". This means that there's a "forward" button to go forward, a "back" button to go backwards, and "left" and "right" buttons to turn the vehicle (ie. in practice the "camera") left and right. This was the most logical control system for such games. After all, you can't have a plane or a car moving sideways, because they just don't move like that in real life either. Basically every single 3D game of the 80's and well into the 90's used this control scheme. It was the most "natural" and ubiquitous way of controlling a 3D game.

Probably because of this, and unfortunately, this control scheme was by large "inherited" into all kinds of 3D games, even when the technology was used in other types of games, such as platformers viewed from third-person perspective, and even first-person shooters.

Yes, Wolfenstein 3D, and even the "grandfather" of first-person shooters, Doom, used "tank controls". There was no mouse support by default (I'm not even sure there was support at all, in the first release versions), and the "left" and "right" keys would turn the camera left and right. There was support for strafing (ie. moving sideways while keeping the camera looking forward), but it was very awkward: Rather than having "strafe left" and "strafe right" buttons, Doom instead had a toggle button to make the left and right buttons strafe. (In other words, if you wanted to strafe, you had to press the "strafe" button and, while keeping it pressed, use the left and right buttons. Just like using the shift key to type uppercase letters.) Needless to say, this was so awkward and impractical that people seldom used it.

Of course all kinds of other 3D games used "tank controls" as well, including many of the first 3D platformers, making them really awkward to play.

For some reason it took the gaming industry a really long time to realize that strafing, moving sideways, was a much more natural and convenient way of moving than being restricted to only being able to move back and forward, and turning the camera. Today we take the "WASD" key mapping, with A and D being strafe buttons, for granted, but this is a relatively recent development. As late as early 2000's some games still hadn't transitioned to this more convenient form of controls.

The same goes to game consoles, by the way. "Tank controls" might even have been even more pervasive and widespread there (usually due to the lack of configurable controller button mapping). There, too, it took a relatively long time before strafing became the norm. The introduction of twin stick controllers made this transition much more feasible, but even then it took a relatively long time before it became the standard.

Take, for example, the game Resident Evil 4, released in 2005 for the PlayStation 2 and the GameCube, both of which had twin stick controllers. The game still used tank controls, and had no strafing support at all. This makes the game horribly awkward and frustrating to control; even infuriatingly so. And this even though modern twin-stick controls had already been the norm for years (for example, Halo: Combat Evolved was published in 2001.)

Nowadays "tank controls" are only limited to games and situations where they make sense. This usually means when driving a car or another similar vehicle, and a few other situations.

And not even always even then. Many tank games, perhaps ironically, do not use "tank controls". Instead, you can move the vehicle freely in the direction pressed with the WASD keys or the left controller stick, while keeping the camera fixated in its current direction, and which can be rotated with the mouse or the right controller stick (and which usually in such games makes the tank aim at that direction). In other words, direction of movement and direction of aiming are independent of each other (and usually the tank aims at the direction that the camera is looking). This makes the game a lot more fluent and practical to play.

The origins of the "Lambada" song

The song "Lambada" by the pop group Kaoma, when released in 1989, was one of these huge hits that people started hating almost as soon as it hit the radio stations, mainly because of being overplayed everywhere.

Back then, its composition was generally misattributed to Kaoma themselves. It wasn't until much later that I heard that was actually just a cover song, not an original one. However, it's actually a bit more interesting than that.

There are, of course constantly hugely popular hits that turn out to be just cover songs by somebody else eg. from the 50's or 60's. This one doesn't go that far back, but it's still interesting.

The original version, "Llorando se Fue" was composed by the Bolivian band Los Kjarkas in 1981. It's originally in Spanish, and while the melody is (almost) the same, the tone is quite different. It uses panflutes, is a bit slower, and is overall very Andean in tone.

See it on YouTube.

This song was then covered by the Peruvian band Cuarteto Continental in 1984. They substituted the panflute with the accordion, already giving it the distinctive tone, and their version is more upbeat and syncopated.

See it on YouTube.

The song was then covered by Márcia Ferreira in 1986. This was an unauthorized version translated to Portuguese, is a bit faster, and emphasizes the syncopation, and is basically identical to the Kaoma version, which was made in 1989.

See it on YouTube.

The Kaoma version, which is by far the best known one, perhaps emphasizes the percussion, and the syncopation even more.

See it on YouTube.

Back then, its composition was generally misattributed to Kaoma themselves. It wasn't until much later that I heard that was actually just a cover song, not an original one. However, it's actually a bit more interesting than that.

There are, of course constantly hugely popular hits that turn out to be just cover songs by somebody else eg. from the 50's or 60's. This one doesn't go that far back, but it's still interesting.

The original version, "Llorando se Fue" was composed by the Bolivian band Los Kjarkas in 1981. It's originally in Spanish, and while the melody is (almost) the same, the tone is quite different. It uses panflutes, is a bit slower, and is overall very Andean in tone.

See it on YouTube.

This song was then covered by the Peruvian band Cuarteto Continental in 1984. They substituted the panflute with the accordion, already giving it the distinctive tone, and their version is more upbeat and syncopated.

See it on YouTube.

The song was then covered by Márcia Ferreira in 1986. This was an unauthorized version translated to Portuguese, is a bit faster, and emphasizes the syncopation, and is basically identical to the Kaoma version, which was made in 1989.

See it on YouTube.

The Kaoma version, which is by far the best known one, perhaps emphasizes the percussion, and the syncopation even more.

See it on YouTube.

The dilemma of difficulty in (J)RPGs

The standard game mechanic that has existed since the dawn of (J)RPGs is that all enemies within given zones have a certain strength (which often varies randomly, but only within a relatively narrow range.) The first zone you start in has the weakest enemies, and they get progressively stronger as you advance in the game and get to new zones.

The idea is, of course, that as the player gains strength from battles (which is the core game mechanic of RPGs), it becomes easier and easier for the player to beat those enemies, and stronger enemies ahead will make the game challenging, as it requires the player to level up in order to be able to beat them. If you ever come back to a previous zone, the enemies there will still be as strong as they were last time, which usually means that they become easier and easier as the player becomes stronger.

This core mechanic, however, has a slight problem: It allows the player to over-level, which will cause the game to become too easy and there not being a meaningful challenge anymore. Nothing is stopping the player, if he so chooses, to spent a big chunk of time in one zone leveling up and gaining strength, after which most of the next zones become trivial because the strength of the enemies are not in par. This may be so even for the final boss of the game.

The final boss is supposed to be the ultimate challenge, the most difficult fight in the entire game. However, if because of the player being over-leveled the final boss becomes trivial, it can feel quite anti-climactic.

This is not just theoretical. It does happen. Two examples of where it has happened to me are Final Fantasy 6 and Bravely Default. At some point by the end parts of both games I got hooked into leveling up... after which the rest of the game until the end became really trivial and unchallenging. And a bit anti-climactic.

One possible solution to this problem that some games have tried is to have enemies level up with the player. This way they always remain challenging no matter how much the player levels up.

At first glance this might sound like a good idea, but it's not ideal either. The problem with this is that it removes the sense of accomplishment from the game; the sense of becoming stronger. It removes that reward of having fought lots of battles and getting stronger from them. There is no sense of achievement. Leveling up becomes pretty much inconsequential.

It's quite rewarding to fight some really tough enemies which are really hard to beat, and then much later and many levels stronger coming back and beating those same enemies very easily. It really gives a sense of having become stronger in the process. It gives a concrete feeling of accomplishment. Remove that, and it will feel futile and useless, like nothing has really been accomplished. The game may also become a bit boring because all enemies are essentially the same, and there is little variation.

One possibility would be if only enemies that the player has yet not encountered before would match the player's level (give or take a few notches), but after they have been encountered the first time in that particular zone they will remain that level for the rest of the game (in that zone). I don't know if this has been attempted in any existing game. It could be an idea worth trying.

All in all, it's not an easy problem to solve. There are always compromises and problems left with all attempted solutions.

The idea is, of course, that as the player gains strength from battles (which is the core game mechanic of RPGs), it becomes easier and easier for the player to beat those enemies, and stronger enemies ahead will make the game challenging, as it requires the player to level up in order to be able to beat them. If you ever come back to a previous zone, the enemies there will still be as strong as they were last time, which usually means that they become easier and easier as the player becomes stronger.

This core mechanic, however, has a slight problem: It allows the player to over-level, which will cause the game to become too easy and there not being a meaningful challenge anymore. Nothing is stopping the player, if he so chooses, to spent a big chunk of time in one zone leveling up and gaining strength, after which most of the next zones become trivial because the strength of the enemies are not in par. This may be so even for the final boss of the game.

The final boss is supposed to be the ultimate challenge, the most difficult fight in the entire game. However, if because of the player being over-leveled the final boss becomes trivial, it can feel quite anti-climactic.

This is not just theoretical. It does happen. Two examples of where it has happened to me are Final Fantasy 6 and Bravely Default. At some point by the end parts of both games I got hooked into leveling up... after which the rest of the game until the end became really trivial and unchallenging. And a bit anti-climactic.

One possible solution to this problem that some games have tried is to have enemies level up with the player. This way they always remain challenging no matter how much the player levels up.

At first glance this might sound like a good idea, but it's not ideal either. The problem with this is that it removes the sense of accomplishment from the game; the sense of becoming stronger. It removes that reward of having fought lots of battles and getting stronger from them. There is no sense of achievement. Leveling up becomes pretty much inconsequential.

It's quite rewarding to fight some really tough enemies which are really hard to beat, and then much later and many levels stronger coming back and beating those same enemies very easily. It really gives a sense of having become stronger in the process. It gives a concrete feeling of accomplishment. Remove that, and it will feel futile and useless, like nothing has really been accomplished. The game may also become a bit boring because all enemies are essentially the same, and there is little variation.

One possibility would be if only enemies that the player has yet not encountered before would match the player's level (give or take a few notches), but after they have been encountered the first time in that particular zone they will remain that level for the rest of the game (in that zone). I don't know if this has been attempted in any existing game. It could be an idea worth trying.

All in all, it's not an easy problem to solve. There are always compromises and problems left with all attempted solutions.

How can 1+2+3+4+... = -1/12?

There's this assertion that has become somewhat famous, as many YouTube videos have been made about it, that the infinite sum of all positive integers equals -1/12. Most people just can't accept it because it seems completely nonsensical and counter-intuitive.

One has to understand, however, that this is not just a trick, or a quip, or some random thing that someone came up at a whim. In fact, historical world-famous mathematicians came to that same conclusion independently of each other, using quite different methodologies. For example, some of the most famous mathematicians of all history, including Leonhard Euler, Bernhard Riemann and Srinivasa Ramanujan, all came to that same result, independently, and using different methods. They didn't just assign the value -1/12 to the sum arbitrarily at a whim, but they had solid mathematical reasons to arrive to that precise value and not something else.

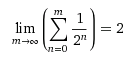

And it is not the only such infinite sum with a counter-intuitive result. There are infinitely many of them. There is an entire field of mathematics dedicated to studying such divergent series. A simple example would be the sum of all the powers of 2:

1 + 2 + 4 + 8 + 16 + 32 + ... = -1

Most people would immediately protest to that assertion. Adding two positive values gives a positive value. How can adding infinitely many positive values not only not give infinity, but a negative value? That's completely impossible!

The problem is that we tend to instinctively think of infinite sums only in terms of its partial finite sums, and the limit that these partial sums approach when more and more terms are added to it. However, this is not necessarily the correct approach. The above sum is not a limit statement, nor is it some kind of finite sum. It's a sum with an infinite number of terms, and partial sums and limits do not apply to it. It's a completely different beast altogether.

Consider the much less controversial statement:

1 + 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 + 1/32 + ... = 2

ie. the sum of the reciprocals of the powers of 2. Most people would agree that the above sum is valid. But why?

To understand why I'm asking the question, notice that the above sum is not a limit statement. In other words, it's not:

This limit is a rather different statement. It is saying that as more and more terms are added to the (finite) sum, the result approaches 2. Note that it never reaches 2, only that it approaches it more and more, as more terms are added.

If it never reaches 2, how can we say that the infinite sum 1 + 1/2 + 1/4 + ... is equal to 2? Not that it just approaches 2, but that it's mathematically equal to it? Philosophical objections to that statement could ostensibly be made. (How can you sum an infinite amount of terms? That's impossible. You would never get to the end of it, because there is no end. The terms just go on and on forever; you would never be done. It's just not possible to sum an infinite number of terms.)

Ultimately, the notation 1 + 1/2 + 1/4 + ... = 2 is a convention. A consensus that mathematics has agreed upon. In other words, we accept the notion that a sum can have an infinite number of terms (regardless of some philosophical objections that could be presented against that idea), and that such an infinite sum can be mathematically equal to a given finite value.

While in the case of convergent series the result is the same as the equivalent limit statement, we cannot use the limit method with divergent series. As much as people seem to accept "infinity" as some kind of valid result, technically speaking it's a nonsensical result, when we are talking about the natural (or even the real) numbers. It's meaningless.

It could well be that divergent sums simply don't have a value, and this may have been what was agreed upon. Just like 0/0 has no value, and no sensible value can be assigned to it, likewise a divergent sum doesn't have a value.

However, it turns out that's not the case. When using certain summation methods, sensible finite values can be assigned to divergent infinite sums. And these methods are not arbitrarily decided on a whim, but they have a strong mathematical reasoning for them. And, moreover, different independent summation methods reach the same result.

We have to understand that a sum with an infinite number of terms just doesn't behave intuitively. It does not necessarily behave like its finite partial sums. The archetypal example often given is:

1 - 1/3 + 1/5 - 1/7 + 1/9 - 1/11 + ... = pi/4

Every term in the sum is a rational number. The sum of two rational numbers gives a rational number. No matter how many rational numbers you add, you always get a rational number. Yet this infinite sum does not give a rational number, but an irrational one. The infinite sum does not behave like its partial sums, nor does it follow the same rules. In other words:

"The sum of two rational numbers gives a rational number": Not necessarily true for infinite sums.

"The sum of two positive numbers gives a positive number": Not necessarily true for infinite sums.

Even knowing all this, you may still have hard time accepting that an infinite divergent sum of positive values not only gives a finite result, but a negative one. We are so strongly attached to the notion of dealing with infinite sums in terms of its finite partial sums that it's hard for us to put aside that approach completely. It's hard to accept that infinite sums do not behave the same as finite sums, nor can they be approached using the same methods.

In the end, it's a question of which mathematical methods you accept on a philosophical level. Just consider that these divergent infinite sums and their finite results are serious methods used by serious professional mathematicians, not just some trickery or wordplay.

More information about this can be found eg. at Wikipedia.

One has to understand, however, that this is not just a trick, or a quip, or some random thing that someone came up at a whim. In fact, historical world-famous mathematicians came to that same conclusion independently of each other, using quite different methodologies. For example, some of the most famous mathematicians of all history, including Leonhard Euler, Bernhard Riemann and Srinivasa Ramanujan, all came to that same result, independently, and using different methods. They didn't just assign the value -1/12 to the sum arbitrarily at a whim, but they had solid mathematical reasons to arrive to that precise value and not something else.

And it is not the only such infinite sum with a counter-intuitive result. There are infinitely many of them. There is an entire field of mathematics dedicated to studying such divergent series. A simple example would be the sum of all the powers of 2:

1 + 2 + 4 + 8 + 16 + 32 + ... = -1

Most people would immediately protest to that assertion. Adding two positive values gives a positive value. How can adding infinitely many positive values not only not give infinity, but a negative value? That's completely impossible!

The problem is that we tend to instinctively think of infinite sums only in terms of its partial finite sums, and the limit that these partial sums approach when more and more terms are added to it. However, this is not necessarily the correct approach. The above sum is not a limit statement, nor is it some kind of finite sum. It's a sum with an infinite number of terms, and partial sums and limits do not apply to it. It's a completely different beast altogether.

Consider the much less controversial statement:

1 + 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 + 1/32 + ... = 2

ie. the sum of the reciprocals of the powers of 2. Most people would agree that the above sum is valid. But why?

To understand why I'm asking the question, notice that the above sum is not a limit statement. In other words, it's not:

This limit is a rather different statement. It is saying that as more and more terms are added to the (finite) sum, the result approaches 2. Note that it never reaches 2, only that it approaches it more and more, as more terms are added.

If it never reaches 2, how can we say that the infinite sum 1 + 1/2 + 1/4 + ... is equal to 2? Not that it just approaches 2, but that it's mathematically equal to it? Philosophical objections to that statement could ostensibly be made. (How can you sum an infinite amount of terms? That's impossible. You would never get to the end of it, because there is no end. The terms just go on and on forever; you would never be done. It's just not possible to sum an infinite number of terms.)

Ultimately, the notation 1 + 1/2 + 1/4 + ... = 2 is a convention. A consensus that mathematics has agreed upon. In other words, we accept the notion that a sum can have an infinite number of terms (regardless of some philosophical objections that could be presented against that idea), and that such an infinite sum can be mathematically equal to a given finite value.

While in the case of convergent series the result is the same as the equivalent limit statement, we cannot use the limit method with divergent series. As much as people seem to accept "infinity" as some kind of valid result, technically speaking it's a nonsensical result, when we are talking about the natural (or even the real) numbers. It's meaningless.

It could well be that divergent sums simply don't have a value, and this may have been what was agreed upon. Just like 0/0 has no value, and no sensible value can be assigned to it, likewise a divergent sum doesn't have a value.

However, it turns out that's not the case. When using certain summation methods, sensible finite values can be assigned to divergent infinite sums. And these methods are not arbitrarily decided on a whim, but they have a strong mathematical reasoning for them. And, moreover, different independent summation methods reach the same result.

We have to understand that a sum with an infinite number of terms just doesn't behave intuitively. It does not necessarily behave like its finite partial sums. The archetypal example often given is:

1 - 1/3 + 1/5 - 1/7 + 1/9 - 1/11 + ... = pi/4

Every term in the sum is a rational number. The sum of two rational numbers gives a rational number. No matter how many rational numbers you add, you always get a rational number. Yet this infinite sum does not give a rational number, but an irrational one. The infinite sum does not behave like its partial sums, nor does it follow the same rules. In other words:

"The sum of two rational numbers gives a rational number": Not necessarily true for infinite sums.

"The sum of two positive numbers gives a positive number": Not necessarily true for infinite sums.

Even knowing all this, you may still have hard time accepting that an infinite divergent sum of positive values not only gives a finite result, but a negative one. We are so strongly attached to the notion of dealing with infinite sums in terms of its finite partial sums that it's hard for us to put aside that approach completely. It's hard to accept that infinite sums do not behave the same as finite sums, nor can they be approached using the same methods.

In the end, it's a question of which mathematical methods you accept on a philosophical level. Just consider that these divergent infinite sums and their finite results are serious methods used by serious professional mathematicians, not just some trickery or wordplay.

More information about this can be found eg. at Wikipedia.

Video games: Why you shouldn't listen to the hype

Consider the recent online multiplayer video game Evolve. It was nominated for six awards at E3, at the Game Critics Awards event. It won four of them (Best of the Show, Best Console Game, Best Action Game and Best Online Multiplayer). Also at Gamescom 2014 it was named the Best Game, Best Console Game Microsoft Xbox, Best PC Game and Best Online Multiplayer Game. And that's just to name a few (it has been reported that the game received more than 60 awards in total.)

Needless to say, the game was massively hyped before release. Some commenters were predicting it to be one of the defining games of the current generation. A game that would shape online multiplayer gaming.

After release, many professional critics praised the game. For example, IGN scored the game 9 out of 10, which is an almost perfect score. Game Informer gave it a score of 8.5 out of 10, and PC Gamer (UK) an 83 out of 100.

(Mind you, these reviews are always really rushed. In most cases reviews are published some days prior to the game's launch. Even when there's an embargo by game publishers, the reviews are rushed to publication on the day of launch or at most a few days later. No publication wants to be late to the party, and they want to inform their readers as soon as they possibly can. With online multiplayer games this can backfire spectacularly because the reviewers cannot possibly know how such a game will pan out when released to the wider public.)

So what happened?

Extreme disappointment by gamers, that's what. Within a month the servers were pretty much empty, and you were lucky if you were able to play a match with competent players. Or anybody at all.

It turns out the game was much more boring, and much smaller in scope, that the hype had led people to believe. And it didn't exactly help that the publisher got greedy and rid the game with outrageously expensive and sometimes completely useless DLC. (For example getting one additional monster to play, something that normally would be just given from the start in this kind of game, cost $15. Many completely useless extremely minor cosmetic DLC, such as a weapon with a different texture, but otherwise identical in functionality to existing weapons, cost $2.)

In retrospect, many reviewers have considered Evolve to be one of the most disappointing games of 2015, which didn't live up even close to its pre-launch hype.

What does this tell us? That pre-launch awards mean absolutely nothing, especially when we are talking about online multiplayer games. Pre-launch hype means absolutely nothing, and shouldn't be believed.

Needless to say, the game was massively hyped before release. Some commenters were predicting it to be one of the defining games of the current generation. A game that would shape online multiplayer gaming.

After release, many professional critics praised the game. For example, IGN scored the game 9 out of 10, which is an almost perfect score. Game Informer gave it a score of 8.5 out of 10, and PC Gamer (UK) an 83 out of 100.

(Mind you, these reviews are always really rushed. In most cases reviews are published some days prior to the game's launch. Even when there's an embargo by game publishers, the reviews are rushed to publication on the day of launch or at most a few days later. No publication wants to be late to the party, and they want to inform their readers as soon as they possibly can. With online multiplayer games this can backfire spectacularly because the reviewers cannot possibly know how such a game will pan out when released to the wider public.)

So what happened?

Extreme disappointment by gamers, that's what. Within a month the servers were pretty much empty, and you were lucky if you were able to play a match with competent players. Or anybody at all.

It turns out the game was much more boring, and much smaller in scope, that the hype had led people to believe. And it didn't exactly help that the publisher got greedy and rid the game with outrageously expensive and sometimes completely useless DLC. (For example getting one additional monster to play, something that normally would be just given from the start in this kind of game, cost $15. Many completely useless extremely minor cosmetic DLC, such as a weapon with a different texture, but otherwise identical in functionality to existing weapons, cost $2.)

In retrospect, many reviewers have considered Evolve to be one of the most disappointing games of 2015, which didn't live up even close to its pre-launch hype.

What does this tell us? That pre-launch awards mean absolutely nothing, especially when we are talking about online multiplayer games. Pre-launch hype means absolutely nothing, and shouldn't be believed.

Steam Controller second impressions

I wrote earlier a "fist impressions" blog post, about a week or two after I bought the Steam Controller. Now, several months later, here are my impressions with more actual experience using the controller.

It turns out that the controller is a bit of a mixed bag. With some games it works and feels great, much better than a traditional (ie. Xbox 360 style) gamepad, in other games not so much. The original intent of the controller was to be a complete replacement of a traditional gamepad, and even the keyboard+mouse mode of control (although to be fair it was never claimed that it would be as good as keyboard+mouse, only that it would be good enough as a replacement, so that you could play while sitting on a couch, rather than having to sit at a desk). With some games it fulfills that role, with others not really.

When it works, it works really well, and I much prefer it over a traditional gamepad. Most usually this is the case with games that are primarily designed for gamepads, but support gamepad and mouse simultaneously (mouse for turning the camera, gamepad for everything else). In this kind of game, especially ones that require even a modicum of accurate aiming, the right trackpad feels so much better than a traditional thumbstick, especially when coupled with gyro aiming. (Obviously at first it takes a bit of getting used to, but once you do, it becomes really fluent and natural.)

As an example, I'm currently playing Rise of the Tomb Raider. For the sake of experimentation, I tried to play the game both with an Xbox 360 gamepad and the Steam Controller, and I really prefer the latter. Even with many years of experience with the former, aiming with a thumbstick is always so awkward and difficult, and the trackpad + gyro make it so much easier and fluent. Also turning around really fast is difficult with a thumbstick (because turning speed necessarily has an upper limit), while a trackpad has in essence no such limitation. You can turn pretty much as fast as you physically can (although the edge of the trackpad is the only limiting factor on how much you can turn in one sweep; however turning speed is pretty much unlimited.)

Third-person perspective games designed primarily to be played with a gamepad are one thing, but how about games played from first-person perspective? It really depends on the game. In my experience the Steam Controller can never reach the same level of fluency, ease and accuracy as the mouse, but with some games it can reach a high-enough degree that playing the game is very comfortable and natural. Portal 2 is a perfect example.

If I had to rate the controller on a scale from 0 to 10, where 10 represents keyboard+mouse, 0 represents something almost unplayable (eg. keyboard only), and 5 represents an Xbox 360 controller, I would put the Steam Controller around 8. Although as said, it depends on the game.

There are some games, even those primarily designed to be played with a gamepad, where the Steam Controller does not actually feel better than a traditional gamepad, but may even feel worse.

This is most often the case with games that do not support gamepad + mouse at the same time, and will only accept gamepad input only. In this case the right thumbstick needs to be emulated with the trackpad. And this seldom works fluently.

The pure "thumbstick emulation" mode just can't compete with an actual thumbstick, because it lacks that force feedback that the springlike mechanism of an actual thumbstick has. When you use a thumbstick, you get tactile feedback on which direction you are pressing, and you get physical feedback on how far you are pressing. The trackpad just lacks this feedback, which makes it less functional.

The Steam Controller also has a "mouse joystick" mode, in which you can emulate the thumbstick, but control it like it were a trackpad/mouse instead. In other words, in principle it works like it were an actual trackpad, using the same kind of movements. This works to an extent, but it's necessarily limited. One of the major reasons is what I mentioned earlier: With a real trackpad control there is no upper limit to your turning speed. However, since a thumbstick has by necessity an upper limit, this emulation mode has that as well. Therefore when you instinctively try to turn faster than a certain threshold, it just won't, so it feels unnatural and awkward, like it had an uncomfortable negative acceleration. Even if you crank the thumbstick sensitivity to maximum within the game, it never fully works. There's always that upper limit, destroying the illusion of the mouse emulation.

With some games it just feels more comfortable and fluent to use the traditional gamepad. Two examples of this are Dreamfall Chapters and Just Cause 2.

As for the slightly awkwardly positioned ABXY buttons, I always suspected that one gets used to them with practice, and I wasn't wrong. The more you use the controller, the less difficult it becomes to use those four buttons. I still wish they were more conveniently placed, but it's not that bad.

So what's my final verdict? Well, I like the controller, and I do not regret buying it. Yes, there are some games where the Xbox360-style controller feels and works better, but likewise there are many games where it's the other way around, and with those the Steam controller feels a lot more versatile and comfortable (especially in terms of aiming, which is usually significantly easier).

It turns out that the controller is a bit of a mixed bag. With some games it works and feels great, much better than a traditional (ie. Xbox 360 style) gamepad, in other games not so much. The original intent of the controller was to be a complete replacement of a traditional gamepad, and even the keyboard+mouse mode of control (although to be fair it was never claimed that it would be as good as keyboard+mouse, only that it would be good enough as a replacement, so that you could play while sitting on a couch, rather than having to sit at a desk). With some games it fulfills that role, with others not really.

When it works, it works really well, and I much prefer it over a traditional gamepad. Most usually this is the case with games that are primarily designed for gamepads, but support gamepad and mouse simultaneously (mouse for turning the camera, gamepad for everything else). In this kind of game, especially ones that require even a modicum of accurate aiming, the right trackpad feels so much better than a traditional thumbstick, especially when coupled with gyro aiming. (Obviously at first it takes a bit of getting used to, but once you do, it becomes really fluent and natural.)

As an example, I'm currently playing Rise of the Tomb Raider. For the sake of experimentation, I tried to play the game both with an Xbox 360 gamepad and the Steam Controller, and I really prefer the latter. Even with many years of experience with the former, aiming with a thumbstick is always so awkward and difficult, and the trackpad + gyro make it so much easier and fluent. Also turning around really fast is difficult with a thumbstick (because turning speed necessarily has an upper limit), while a trackpad has in essence no such limitation. You can turn pretty much as fast as you physically can (although the edge of the trackpad is the only limiting factor on how much you can turn in one sweep; however turning speed is pretty much unlimited.)

Third-person perspective games designed primarily to be played with a gamepad are one thing, but how about games played from first-person perspective? It really depends on the game. In my experience the Steam Controller can never reach the same level of fluency, ease and accuracy as the mouse, but with some games it can reach a high-enough degree that playing the game is very comfortable and natural. Portal 2 is a perfect example.

If I had to rate the controller on a scale from 0 to 10, where 10 represents keyboard+mouse, 0 represents something almost unplayable (eg. keyboard only), and 5 represents an Xbox 360 controller, I would put the Steam Controller around 8. Although as said, it depends on the game.

There are some games, even those primarily designed to be played with a gamepad, where the Steam Controller does not actually feel better than a traditional gamepad, but may even feel worse.

This is most often the case with games that do not support gamepad + mouse at the same time, and will only accept gamepad input only. In this case the right thumbstick needs to be emulated with the trackpad. And this seldom works fluently.

The pure "thumbstick emulation" mode just can't compete with an actual thumbstick, because it lacks that force feedback that the springlike mechanism of an actual thumbstick has. When you use a thumbstick, you get tactile feedback on which direction you are pressing, and you get physical feedback on how far you are pressing. The trackpad just lacks this feedback, which makes it less functional.

The Steam Controller also has a "mouse joystick" mode, in which you can emulate the thumbstick, but control it like it were a trackpad/mouse instead. In other words, in principle it works like it were an actual trackpad, using the same kind of movements. This works to an extent, but it's necessarily limited. One of the major reasons is what I mentioned earlier: With a real trackpad control there is no upper limit to your turning speed. However, since a thumbstick has by necessity an upper limit, this emulation mode has that as well. Therefore when you instinctively try to turn faster than a certain threshold, it just won't, so it feels unnatural and awkward, like it had an uncomfortable negative acceleration. Even if you crank the thumbstick sensitivity to maximum within the game, it never fully works. There's always that upper limit, destroying the illusion of the mouse emulation.

With some games it just feels more comfortable and fluent to use the traditional gamepad. Two examples of this are Dreamfall Chapters and Just Cause 2.

As for the slightly awkwardly positioned ABXY buttons, I always suspected that one gets used to them with practice, and I wasn't wrong. The more you use the controller, the less difficult it becomes to use those four buttons. I still wish they were more conveniently placed, but it's not that bad.

So what's my final verdict? Well, I like the controller, and I do not regret buying it. Yes, there are some games where the Xbox360-style controller feels and works better, but likewise there are many games where it's the other way around, and with those the Steam controller feels a lot more versatile and comfortable (especially in terms of aiming, which is usually significantly easier).

When video game critics and I disagree

Every year, literally thousands of new video games are published. Even if we discard completely sub-par amateur trash, we are still talking about several hundreds of video games every year that could potentially be very enjoyable to play. It is, of course, impossible to play them all, not to talk about it being really expensive. There are only so many games one has the physical time to play.

So how to choose which games to buy and play? This is where the job of video game critics comes into play. If a game gets widespread critical acclaim, there's a good chance that it will be really enjoyable. If it gets negative reviews, there's a good chance that the game is genuinely bad and unenjoyable.

A good chance. But only that.

And that's sometimes the problem. Sometimes I buy a game expecting it to be really great because it has received such universal acclaim, only to find out that it's so boring or so insufferable that I can't even finish it. Sometimes such games even make me stop playing them in record time. (As I have commented many times in previous blog posts, I hate leaving games unfinished. I often even grind through unenjoyable games just to get them finished, because I hate so much leaving them unfinished. A game has to be really, really bad for me to give up. It happens relatively rarely.)

As an example, Bastion is a critically acclaimed game, with very positive reviews both from critics and the general gaming public. I could play it for two hours before I had to stop. Another example is Shovel Knight. The same story repeats, but this time I could only play for 65 minutes. Especially the latter was so frustrating that I couldn't bother to play it. (And it's not a question of it being "retro", or 2D, or difficult. I like difficult 2D platformer games when they are well made. For example, I loved Ori and the Blind Forest, as well as Aquaria, Xeodrifter and Teslagrad.)

Sometimes it happens in the other direction. As an example, I just love the game Beyond: Two Souls for the PS4. When I started playing it, it was so engaging that I played about 8 hours in one sitting. I seldom do that. While the game mechanics are in some aspects a bit needlessly limited, that's only a very small problem in an otherwise excellent game.

Yet this game has received quite mixed reviews, with some reviewers being very critical of it. For example, quoting Wikipedia:

IGN gaming website criticised the game for offering a gaming experience too passive and unrewarding and a plot too muddy and unfocused. Joystiq criticised the game's lack of solid character interaction and its unbelievable, unintentionally silly plot. Destructoid criticised the game's thin character presentation and frequent narrative dead ends, as well as its lack of meaningful interactivity. Ben "Yahtzee" Croshaw of Zero Punctuation was heavily critical of the game, focusing on the overuse of quick time events, the underuse of the game's central stealth mechanics, and the inconsistent tone and atmosphere.And:

In November 2014, David Cage discussed the future of video games and referred to the generally negative reviews Beyond received from hardcore gamers.Needless to say, I completely disagree with those negative reviews. If I had made my purchase decision (or, in this case, the decision not to purchase) based on these reviews, I would have missed one of the best games I have ever played. And that would have been a real shame.

This is a real dilemma. How would I know if I would enjoy, or not enjoy, a certain game? I can mostly rely only on reviews, but sometimes I find out that I completely disagree with them. This both makes me buy games that I don't enjoy, and probably makes me miss games that I would enjoy a lot.

The genius of Doom and Quake

I have previously written about id Software, and wondered what happened to them. They used to be pretty much at the top of the PC game developers (or at the very least, part of the top elite). Their games were extremely influential in PC gaming, especially the first-person shooter genre, and they were pretty much the company that made the genre what it is today. While perhaps not necessarily the first ones to invent all the ideas, they definitely invented a lot of them, and did it right, and their games are definitely the primary source from which other games of the genre got their major game mechanics. Most action-oriented (and even many non-action oriented) first-person shooter games today use most of the same basic gameplay designs that Doom and especially Quake invented, or at least helped popularize.

But what made them so special and influential? Let me discuss a few of these things.

We have to actually start from id Software's earlier game, Wolfenstein 3D. The progression is not complete without mentioning it. This game was still quite primitive in terms of the first-person shooter genre, both with severe technical limitations, as well as gameplay limitations, as the genre was still finding out what works and what doesn't. One of the things that Wolfenstein 3D started to do, is to make the first-person perspective game a fast-paced one.

There had been quite many games played from the first-person perspective before Wolfenstein 3D, but the vast majority (if not all) of them were very slow-paced and awkward, and pretty much none of them had the player actually aim by moving the camera (with some possible exceptions). There were already some car and flight simulators and such, but they were not shooters really. Even the airplane shooter genre played from the first-person perspective were usually a bit awkward and sluggish, and they usually lacked that immersion, that real sense of seeing the world from the first-person perspective. (In most cases this was, of course, caused by the technical limitations of the hardware of the time.)

Wolfenstein might not have been the first game that started the idea of a fast-paced shooter from the first-person perspective, where you aim by moving the camera, but it certainly was one of the most influential ones. Although not even nearly as influential as id Software's first huge hit, Doom.

Doom was even more fast-paced, had more and tougher enemies, and was even grittier. (It of course helped that game engine technology had advanced by that point to allow a much grittier environment, with a bit more realism). And gameplay in Doom was fast! It didn't shy away from having the playable character (ie. in practice the "camera") run at a superhuman speed. And it was really a shooter. Tons of enemies (especially with the hardest difficulty), and fast-paced shooting action.

Initially Doom was still experimenting with its control scheme. It may be hard to imagine it today, but originally Doom was controlled with the cursor keys, with the left and right cursors actually turning the camera, rather than strafing. There was, in fact, no strafe buttons at all. There was a button which, when pressed, allowed you to strafe by pressing the left and right cursor keys (ie. a kind of mode switch button), but it was really awkward to use. By this point there was still no concept of the nowadays ubiquitous WASD key scheme (with the A and D keys being for strafing left and right).

In fact, there was no mouse support at all at first. Even later when they added it, it was mostly relegated to a curiosity for most players. As hard as it might be to believe, the concept of actually using the mouse to control the camera had yet not been invented for first-person shooters. It was still thought that you would just use the cursor keys to move forward and back, and turn the camera left and right (ie. so-called "tank controls").

Of course since it was not possible to turn the camera up or down, the need for a mouse to control the camera was less.

Strafing in first-person shooters is nowadays an essential core mechanic, but not back in the initial years of Doom.

Quake was not only a huge step forward in terms of technology, but also in terms of gameplay and the control scheme. However, once again, as incredible as it might sound, the original Quake still was looking for that perfect control scheme that we take so much for granted today. If you were to play the original Quake, the control scheme would still be very awkward. But it was already getting there. (For example, now the mouse could be used by default to turn the camera, but only sideways. You had to press a button to have free look... which nowadays doesn't make much sense.) It wouldn't be until Quake 2 that we get pretty much the modern control scheme (even though with the original version of the game the default controls still were a bit awkward, but mostly configurable to a modern standard setup.)

Quake could, perhaps, be considered the first modern first-person shooter (other than for its awkward control scheme; which was fixed in later iterations, mods and ports). It was extremely fast-paced, with tons of enemies, tons of shooting, tons of explosions and tons of action. It also pretty much established the keyboard+mouse control scheme as the standard scheme for the genre. Technically it of course looks antiquated (after all, the original Quake wasn't even hardware-accelerated; everything was rendered using the CPU, which in that time meant the Pentium. The original one. The 60-MHz one.) However, the gameplay is very reminiscent of a modern FPS game.

Doom and especially Quake definitely helped define an entire (and huge) genre of PC games (a genre that has been so successful, that it has even become a staple of game consoles, even though you don't have a keyboard and mouse there.) They definitely did many things right, and have their important place in the history of video games.

But what made them so special and influential? Let me discuss a few of these things.

We have to actually start from id Software's earlier game, Wolfenstein 3D. The progression is not complete without mentioning it. This game was still quite primitive in terms of the first-person shooter genre, both with severe technical limitations, as well as gameplay limitations, as the genre was still finding out what works and what doesn't. One of the things that Wolfenstein 3D started to do, is to make the first-person perspective game a fast-paced one.

There had been quite many games played from the first-person perspective before Wolfenstein 3D, but the vast majority (if not all) of them were very slow-paced and awkward, and pretty much none of them had the player actually aim by moving the camera (with some possible exceptions). There were already some car and flight simulators and such, but they were not shooters really. Even the airplane shooter genre played from the first-person perspective were usually a bit awkward and sluggish, and they usually lacked that immersion, that real sense of seeing the world from the first-person perspective. (In most cases this was, of course, caused by the technical limitations of the hardware of the time.)

Wolfenstein might not have been the first game that started the idea of a fast-paced shooter from the first-person perspective, where you aim by moving the camera, but it certainly was one of the most influential ones. Although not even nearly as influential as id Software's first huge hit, Doom.

Doom was even more fast-paced, had more and tougher enemies, and was even grittier. (It of course helped that game engine technology had advanced by that point to allow a much grittier environment, with a bit more realism). And gameplay in Doom was fast! It didn't shy away from having the playable character (ie. in practice the "camera") run at a superhuman speed. And it was really a shooter. Tons of enemies (especially with the hardest difficulty), and fast-paced shooting action.

Initially Doom was still experimenting with its control scheme. It may be hard to imagine it today, but originally Doom was controlled with the cursor keys, with the left and right cursors actually turning the camera, rather than strafing. There was, in fact, no strafe buttons at all. There was a button which, when pressed, allowed you to strafe by pressing the left and right cursor keys (ie. a kind of mode switch button), but it was really awkward to use. By this point there was still no concept of the nowadays ubiquitous WASD key scheme (with the A and D keys being for strafing left and right).

In fact, there was no mouse support at all at first. Even later when they added it, it was mostly relegated to a curiosity for most players. As hard as it might be to believe, the concept of actually using the mouse to control the camera had yet not been invented for first-person shooters. It was still thought that you would just use the cursor keys to move forward and back, and turn the camera left and right (ie. so-called "tank controls").

Of course since it was not possible to turn the camera up or down, the need for a mouse to control the camera was less.

Strafing in first-person shooters is nowadays an essential core mechanic, but not back in the initial years of Doom.

Quake was not only a huge step forward in terms of technology, but also in terms of gameplay and the control scheme. However, once again, as incredible as it might sound, the original Quake still was looking for that perfect control scheme that we take so much for granted today. If you were to play the original Quake, the control scheme would still be very awkward. But it was already getting there. (For example, now the mouse could be used by default to turn the camera, but only sideways. You had to press a button to have free look... which nowadays doesn't make much sense.) It wouldn't be until Quake 2 that we get pretty much the modern control scheme (even though with the original version of the game the default controls still were a bit awkward, but mostly configurable to a modern standard setup.)

Quake could, perhaps, be considered the first modern first-person shooter (other than for its awkward control scheme; which was fixed in later iterations, mods and ports). It was extremely fast-paced, with tons of enemies, tons of shooting, tons of explosions and tons of action. It also pretty much established the keyboard+mouse control scheme as the standard scheme for the genre. Technically it of course looks antiquated (after all, the original Quake wasn't even hardware-accelerated; everything was rendered using the CPU, which in that time meant the Pentium. The original one. The 60-MHz one.) However, the gameplay is very reminiscent of a modern FPS game.

Doom and especially Quake definitely helped define an entire (and huge) genre of PC games (a genre that has been so successful, that it has even become a staple of game consoles, even though you don't have a keyboard and mouse there.) They definitely did many things right, and have their important place in the history of video games.

Deceptive 5 stars rating systems

I noticed something funny, and illuminating, when browsing the Apple App Store. One game had this kind of rating:

In other words, 2.5 stars (which is even stated as text as well). This would indicate that the ratings are split pretty evenly. 50% approval rate.

However, the game had four 1-star ratings and two 5-star ratings. 1 star is the minimum rating, and 5 stars is the maximum.

Wait... That doesn't make any sense. That's not an even split. There are significantly more 1-star ratings than 5-star ratings (in fact, double the amount). That's not even close to an even split. Four people rated it at 1 star, and only two at 5 stars.

Is the calculation correct? Well, the weighted average is (4*1+2*5)/(4+2) = 2.333 ≈ 2.5 (we can allow rounding to the nearest half star.)

So the calculation is correct (allowing a small amount of rounding). It is indeed 2.5 stars. The graphic is correct.

But it still doesn't make any sense. How can 4x1 star + 2x5 stars give an even split? That's not possible. There are way more 1-star ratings than 5-star ratings. It can't be an even split! What's going on here?

The problem is that the graphic is misleading. The minimum vote is 1 star, not 0 stars. (If there were a possibility of 0-star ratings, then the graphic would actually be correct.)

The graphic becomes more intuitive if we remove the leftmost star:

Now it looks more intuitive. Now it looks like it better corresponds to the 4x1 - 2x5 split. In other words, a bit less than 50% rating.

Or to state it in another way: The problem is that the leftmost star is always "lit", regardless of what the actual ratings are, which gives a misleading and confusing impression.

In reality the rating system should be thought of as being in the 0-4 range (rather than 1-5), with only four stars, and the possibility of none of them being "lit". Then it becomes more intuitive and gives a better picture of how the ratings are split.

As it is, with a range of 1-5, with the leftmost star always "lit", it gives the false impression of the ratings being higher than they really are. I don't know if they do this deliberately, or if they just haven't thought of this.

In other words, 2.5 stars (which is even stated as text as well). This would indicate that the ratings are split pretty evenly. 50% approval rate.

However, the game had four 1-star ratings and two 5-star ratings. 1 star is the minimum rating, and 5 stars is the maximum.

Wait... That doesn't make any sense. That's not an even split. There are significantly more 1-star ratings than 5-star ratings (in fact, double the amount). That's not even close to an even split. Four people rated it at 1 star, and only two at 5 stars.

Is the calculation correct? Well, the weighted average is (4*1+2*5)/(4+2) = 2.333 ≈ 2.5 (we can allow rounding to the nearest half star.)

So the calculation is correct (allowing a small amount of rounding). It is indeed 2.5 stars. The graphic is correct.

But it still doesn't make any sense. How can 4x1 star + 2x5 stars give an even split? That's not possible. There are way more 1-star ratings than 5-star ratings. It can't be an even split! What's going on here?

The problem is that the graphic is misleading. The minimum vote is 1 star, not 0 stars. (If there were a possibility of 0-star ratings, then the graphic would actually be correct.)

The graphic becomes more intuitive if we remove the leftmost star:

Now it looks more intuitive. Now it looks like it better corresponds to the 4x1 - 2x5 split. In other words, a bit less than 50% rating.

Or to state it in another way: The problem is that the leftmost star is always "lit", regardless of what the actual ratings are, which gives a misleading and confusing impression.

In reality the rating system should be thought of as being in the 0-4 range (rather than 1-5), with only four stars, and the possibility of none of them being "lit". Then it becomes more intuitive and gives a better picture of how the ratings are split.

As it is, with a range of 1-5, with the leftmost star always "lit", it gives the false impression of the ratings being higher than they really are. I don't know if they do this deliberately, or if they just haven't thought of this.

The genius of Pokémon games

The Pokémon games celebrate their 20-year anniversary this year. There are currently six "generations" of these games; each generation consists one or two complementary pairs of games (each pair is essentially the same game, but with some catchable

pokémon being different, and some details in the storyline changed), and a third individual game in some cases. If we count each complementary pair of games as essentially the same game, there are 16 distinct games in total (27 if we count all games individually). This is, of course, only counting the core games, not the side games nor spinoffs (which usually are of a completely different genre and use completely different game mechanics.)

Curiously, each of the core games uses essentially the exact same basic game mechanic. From the very first games of generation 1 to the latest games of generation 6.

Describing the common aspects of the game mechanics of all the games would be too long, but to pick up the most essentials, it's basically a turn-based JRPG with a party of at most 6 pokémon, each with at most 4 moves, them being able to learn new moves as they level up, or using special items. Pokémon belong to different "classes" with a rock-paper-scissors system of strengths and weaknesses against other such "classes". Wild pokémon can be defeated for exp, or caught and added to the player's roster. The core story consists of the protagonist starting with one starter pokémon and advancing from city to city, challenging gym leaders, and ultimately reaching the Pokémon League where they will fight the "Elite Four", as the ultimate challenge and "soft end" of the game (although in most of the games the gameplay will continue after that with additional side quests and goals, and often even expanded world and new catchable pokémon.) There are a myriad of other staples and stock features that appear in all of the games, but I won't make this paragraph any longer by listing them.

Every single core game in the series, all 27 of them (so far), use the that exact same core game mechanic, and follow that same core plot. All of them. Their graphics have advanced with the hardware (even making a quite successful jump to 3D), and each new generation has additional features to them (lots of new pokémon, new battle modes, new side quests, etc.) but essentially all follow the same pattern. One could pretty much say that if you have played one of them, you have played all of them.

Yet, somehow, against all logic, each game is as enjoyable to play as ever. Somehow they avoid a sense of endless repetition, even though that would describe them quite well. I have a hard time explaining why. That's the genius behind these games.